053: A Conversation with Cynthia Merhej

The Renaissance Renaissance designer on resilience and alter egos

Cynthia Merhej joins our call from her atelier in Beirut. She is wearing a light heather grey t-shirt that is anything but ordinary from her brand, Renaissance Renaissance, but she also likes to buy children’s t-shirts in bulk from Beirut’s Cotton Mall. Cynthia’s mother, Laura Merhej, is not at the atelier when we speak. Laura is an established designer herself, and has been in the business for nearly thirty years. Cynthia credits her mother for much of what she’s learned as a designer, having spent her childhood in Laura’s atelier. Now the two work side by side, bringing to life romantic but smart incomparable clothing whose references range from 17th century Arab clothing and poppies, to the Japanese designers who arrived on the scene in the 1980s.

In February of this year, Renaissance Renaissance was selected as a semi-finalist for the competitive LVMH Prize. The brand’s stockists include Dover Street Market London, SSENSE, and Harrods. Cynthia’s works have been worn by Lady Gaga, Caroline Polachek, Dua Lipa, and Chloë Sevigny, and she has designed costumes for director Durga Chew-Bose’s debut film, Bonjour Tristesse. In an industry known for swollen egos, with such prestigious accomplishments under her belt, Cynthia is astonishingly humble. What is, however, most stunning, is that these achievements are born of the efforts of just three women: Cynthia, Laura, and their seamstress, Nona.

Tasnim: How are you doing? Are you in Beirut?

Cynthia: I'm good. I'm in Beirut at our atelier. This is where my mom worked for about thirty years, and this is where I'm working now with her.

T: How are things right now in Lebanon?

C: It's gotten much better since there was a ceasefire. When there was a ceasefire back in November…well, it's not really a ceasefire; there’s still bombing every day. But when that happened, it gave me hope for the first time in a long time, and I was like, okay, let's do this, let's move back. It's been very difficult because you face all the same challenges that every other designer faces anywhere else, plus you're in a country that has a very corrupt ruling class, and so there's basically no infrastructure for anything. We don't have electricity full time here. We don't have running water full time. We don't have the internet full time.

A lot of things that maybe are taken for granted in the West, here we don't have. It's kind of crazy how much that actually affects your ability on a day to day basis, just to function and work and keep up with the rest of the world. I think what is really special here is despite all the hardships we've faced, especially in the last five years, it's amazing how kind and helpful people still are, and how quickly they adapt. We had Covid and a financial crisis where we literally lost our money overnight, myself included. Then there was the explosion. It all happened in the same year. We had very violent protests and crackdowns on protests.

There was a lot of uncertainty and huge inflation. We had absolutely no supplies, because there was no money, no gas for cars, or electricity. Then the wars in Gaza and then Lebanon. It was one after the other. I think if only one of those things happened anywhere else, people would go crazy. Here, it's really beautiful to see how people still maintain their humanity despite all of these things. I mean, it's not a perfect country, but it's still really nice to work here, even with everything going on, because of this aspect of humanity.

T: What gives you the motivation to keep pushing forward with the brand and the work?

C: Because I don't know how else I would do what I love. I started this because I really love fashion and creative direction. It made sense to start a brand because I didn't see anyone like me running a brand. I didn't see many other options, so I was like, let me start my own thing.

T: You originally studied visual communication at Central Saint Martins; what inspired you to change course and become a fashion designer?

C: It was very natural, having grown up in this space. This is where I spent a lot of my time as a child, but I also loved storytelling. My favorite things to do as a child were reading books, dressing my sisters, making up stories and directing my sisters in them. Then I had this epiphany one day where I thought, this feels really shallow. I was also becoming a teenager, and reading a lot about imperialism, capitalism, American hegemony, et cetera. So I thought maybe I should do something else.

I was trying all kinds of creative endeavors, but realized that I love everything. I love directing. I love having a big story to tell and being able to draw on a lot of different tools to tell that story. When I was doing visual communication, it was very limiting. It was very frustrating because every avenue felt limited, and there was no fashion in them. I was starting to get back into fashion when I left Lebanon because I finally had access to things that I didn’t have before. I had outgrown teen fashion magazines, and my mum wouldn't buy serious fashion magazines for me. When I got to London, I was like, yes, I'm free to buy Vogue now.

In London, I had the opportunity to find other magazines like Pop, for example. I was obsessed with Pop because it wasn’t just about fashion, it was also intellectual, with amazing essays in it. I was finally able to expose myself to things like that. I immediately got back into fashion, but it became kind of like a thing I had no one to talk to. In visual communication, no one cared about things like the new Balenciaga collection.

I'm really happy I didn't study fashion at Central Saint Martins, because I think it's a very specific program. Having taught in fashion schools since coming back to Lebanon, the thing about fashion school, you’re told to do whatever you want, but it's also implied you have to do what we think is good or else you don't make it into the show. Or you don't make it because you don't get the same opportunities that other students had, especially at Central Saint Martins.

It just seemed like there was a very specific way of doing things, and if you don't do it that way, you'll basically be forgotten. By the end of my studies, I realized I was really into fashion and creating. I didn't know what creative direction was, which is so stupid that no one told me it was a job. All the times I had meetings with my teachers and they told me to choose: Do you want to do illustration or do you want to do film? I liked them all. I realized what I wanted to do and that I wanted to do it in fashion. There were no Arabs, no women in any of these fashion houses. So what were my chances? I didn’t have a fashion portfolio. I didn’t have any of the stereotypical credentials or connections to get in the door.

It was a matter of what the fastest way to getting to where I wanted was, and that was coming back home. So I came back. I worked to make money so I could start this brand. When I left my full time job after two years, I was doing a million other jobs to support myself.

T: How did you know how to cut patterns?

C: I had to learn everything. I approached it like I was going back to school again, except I was creating my own curriculum. It wasn't easy in the beginning; I was feeling very insecure about the fact that I didn't go to fashion school, that no one was going to take me seriously. I even tried to apply for a master's at some point, and thankfully got rejected. And then I was like, fuck this. I don't need to go to school again for someone to tell me I'm good.

T: Were you picking things up as you were spending time in your mom's atelier or were you doing classes outside of that?

C: I was doing classes. I have ADHD, and my mum is not a very patient person. I can barely concentrate on things that are very repetitive or manual, so that makes it even harder for me. She'll explain something and I can't absorb it. She's been doing it for thirty years. We're just on totally different wavelengths. It's like someone who was a physicist talking to a kindergartner. I took pattern making classes, which helped me understand the logic behind things. I took drawing classes, practiced during my free time, and watched a lot of videos to try to figure out how to do something.

My mum would take something that maybe already existed or was a straightforward cut, but for her it was more about the fabrics and trimmings. Whereas I'm thinking about the construction of the garment, about the silhouette, and creating a certain shape that doesn’t exist. So we have to make it from scratch, and my mum’s not used to working on a pattern totally from scratch. I had to learn how to execute things, because she would be like, oh, that's not possible. And I'd be like, yeah, it is.

T: When I spoke to Durga (Chew-Bose), she said that you have this really great eye for couture and costume. Where did that come from?

C: The couture aspect is related to my mum and having grown up in this environment where you have a very acute awareness of how things are made, and how things are made well. She’s really into quality, making things that last, making things properly, getting the right fabrics. It's not about quantity, it's about quality. These things have been drilled into my head. She has, in a way, that traditional sense of making things.

I’m not traditional in the way I think or as a person. My mom is traditional about craft, this is done like this because X, Y, Z. And I’m like, but why? If you say the words raw edge in this atelier…it took maybe three years for that to be accepted here. That was a crazy, crazy idea.

T: I'm curious: when you were younger, how did you like to dress up?

C: Oh, my god. I was very specific. Something that used to drive me crazy was that my mum would like to dress us up, and I hated that. I was very specific about the things I liked. Those are probably some of my most traumatizing memories, if I wasn't allowed to wear the thing I wanted to wear. My concept of fashion was so bizarre. I'd be convinced that something was so cool, and I’d go to school and no one thought it was cool.

T: Well, that's how you know it's really cool. When you were younger, was your mom making clothes for you?

C: She didn't really have time. She had three kids and her own business, so she didn't really have time to make things for us. The only time I asked her to make something for me was because of the Tom Ford Gucci collection with the velvet suits. I became obsessed with having velvet suits.

T: Did she make it for you?

C: She made me velvet bell-bottoms. I was very picky about it.

T: I was obsessed with a Tom Ford top. I saw a picture at a tailor’s shop when I was a teenager, and it had long bell sleeves. In Bangladesh, we didn't have the kinds of materials that Tom Ford was using, so I bought this black cotton fabric that had a raised textured pattern that looked similar. My mum and I went to the tailor maybe five or six times to have it made. And then once it was made, I never wore it. It was just the satisfaction of having it. I still have it.

C: I wish I had those pants now. But what fucking weirdo eleven year old wants to wear a velvet suit? In my head, I was like, this is so cool. It's Tom Ford, but nobody in my school knew the reference or got it. Everyone's in jeans and you're there in little velvet outfits. But I liked it. I felt like I looked really cool.

My style was very weird, and I didn’t have a big selection of clothes. I have two sisters, but one sister is four years younger, and my older sister was very attached to her things. There were a lot of hand-me-downs, and my closet was a mishmash of things. It's kind of funny because my closet is still kind of like that. I would love to have a curated closet, but I still can't afford to have it.

I don't want to spend one hundred dollars on a cotton T-shirt because it's the “best” cotton t-shirt made. I'll go to the Cotton Mall here. It’s my heaven; they have boxers, flannels, long sleeve t-shirts, kids t-shirts. I'll go to the kids section and buy ten T-shirts for five dollars, and they're as good as those expensive t-shirts. I get special pieces from my friends, other designers, from their line sheets.

It was actually great that my parents couldn't afford to buy us things or wouldn’t just out of principle. They'd say, it costs so much money just because it's Puma, but we don't care, so figure it out. I had to just try to use whatever I had to make a look.

T: It forces you to think creatively. How can I replicate it with the budget I have?

C: There was one magazine called Elle Girl, which I was obsessed with. They had a section where they would photograph people around the globe. Street style outfits. It was super inspirational because it was just people in their normal clothes. I’d think, maybe I can do that. I was just trying to make do with what I had.

T: How did your mom get started with setting up her atelier?

C: When she was a kid, she just sat on a sewing machine and started sewing. She made little outfits for her dolls, and was into crochet and sewing her own clothes. She lived in the States for a period of time, and when she was there, she had access to lots of patterns, and could go to the discount store and buy fabrics for really cheap. She made her own clothes. It’s been her passion.

When she moved back to Beirut, people were asking her, where's your outfit from? At the time, there was a civil war going on, and she set up her atelier. It was a great time to start a business, because there wasn’t anything else, there weren’t a lot of foreign brands here. People were buying from local designers, more than they do today. Even though there was a civil war, people still living their lives. Wherever there would be a safe zone, people would be partying and living their lives there. Then it gets bombed and then that zone moves. People were going out, having dinners and parties. People wanted to dress up.

T: It’s fascinating that with everything that’s happened in Lebanon and seeing how you've also started up your business in the midst of it. If something like that were to happen in the West on that scale, I think society would collapse. There's this inherent resilience in people, in you, in your mom. There is so much going on, but we still need to live life. That's a beautiful thing, that you don't give up on living life to the fullest.

C: I think here we are more realistic about things, because the exploitation is very in your face. Versus in the West, it's very hypocritical. They're exploiting people, but it's usually not in your own country. When it does happen, it's not seen or it’s segregated in a way, in specific areas. Lebanon is a very small country. Everyone's in everyone's face. It's not the easiest place. You can literally see everything falling apart in front of you.

Maybe that's better in a way, because we see things for what they are. Everything is just a bit more out in the open. When things were really hard here, I would think that my mom lived through a civil war. Her mom got kicked out of her own home and had to leave for Lebanon, then also had to live through a civil war. Same with her mom. So I think, they've been through worse, I'll survive.

T: Your great grandmother Laurice Srouji was also a designer of great renown in Palestine, before she was displaced during the Nakba. What kind of work was she doing, and who were her clients?

C: She had her atelier and was doing couture work. She had clients that would come in and ask for dresses for bridal trousseaus because their daughters were getting married. Women would kind of come from different parts of the country to work with her. It was a British mandate at the time, so some of the British mandate wives would also come. It's really sad because we don't have anything left of that place. We just have a picture and a bag full of things like trims and little pieces of fabrics.

T: What was your experience designing costumes for Bonjour Tristesse like?

C: It was a very interesting process. I'd never done a film before, and had no idea going in. I love films. It was always my dream to include film in my brand universe, whether it was producing or directing a film, or even costumes.

T: I came across some articles you wrote a long time ago for Rookie about some of your favourite films.

C: What!? Deep cuts, deep cuts! What did I write about?

T: You did these journals of when you were in Indonesia and there were images from Lebanon, too. Then there were the movies you’d written about. They were these really great, kind of esoteric films that your average person would have never heard about. I thought it was so interesting. So I completely understand just how much you love film.

C: I wrote my thesis on it. I love it. It's a big part of me. I did an interview before we started, and I was saying how film is the closest thing to fashion, in terms of creative direction, because you also have to kind of create a whole universe.

The process with Durga was really nice. I don't know if all films are like this. I doubt it.

T: Was she the one who approached you?

C: She did. David (Siwicki, whose company does PR for Renaissance Renaissance) was already in contact with her and was like, hey, why doesn’t Cynthia do this? She had already heard about the brand and really liked it. It was really flattering. At first I thought, there was no way it could be real. She could probably get any big brand to do it. It’s Bonjour Tristesse, it's a classic French novel. Don't get your hopes up. They’ll probably pick a bigger brand and it'll be over and they'll call and be like, sorry, maybe another time. When things actually started happening, I thought, oh my god, shit. This is happening. This is real. It’s a dream coming true.

It was very collaborative between me, Durga, and Miyako, who was the costume designer, who is amazing. I personally love working that way. We spoke a lot, Miyako would send mood boards, and I would send back ideas. I had a couple of in-person meetings where we just tried things on Miyako and got ideas there.

The process of thinking of just one person versus a whole collection can be really liberating, because when you're designing a collection, there are specific commercial things you have to think about. And when you're thinking of a movie, it's just so intimate. It's trying to understand the psychology of the character. It's kind of easier because it's just one person. You have to think only about that story. You don't think about, for example, if clients in China are going to wear it, or if people don't buy yellow. You have your limitations of the character, but it's also more free.

T: Were you sourcing materials in Lebanon for the costumes?

C: Yes, because we had a very limited budget. For Lily’s (McInerny) dress, there was a very specific shade that Miyako had in mind. She knew that that scene was going to be shot in the dark, so she thought we should make it from something quite light, like a pale yellow or cream. We tried to find a lot of different options for that. I searched here. She searched in New York. We ended up finding the fabric for that dress in New York, but the rest I sourced here.

T: How did you come up with the idea for the dress with the cape? Chloë Sevigny’s character Anne talks about a dress resembling a dandelion, and when I saw the dress with the cape, I thought how it really did look like a dandelion. She looks like she's about to float away.

C: I was experimenting with making this dress maybe three years ago, for Fall/Winter ‘23. I was trying to make a vest with a bubble peplum. The lining wasn't stitched to it, and when I tried it on, the lining fell out. I was like, that's such a cool shape! I should do this with a bunch of other things. I liked this idea of one piece attached to another and that you could wear it in multiple ways. That's something I love to explore in my work. It became a cape, then a cape dress, then a cape jacket.

We decided the dress was already so perfect, and adapted it, adding the tulle element that it didn't have before to make it look more like a flower.

T: How much time did you have?

C: You don't have much time. Apparently we actually started way in advance. We did a lot of research and discussed ideas. Then it’s like we need everything in a week, so you're making dresses overnight. You have to be super resourceful and work with whatever you have, try to find things that already exist you can adapt. I thought of what I could adapt that would work for Anne’s character and work for Chloe's body type as well? I have to think of the women, the actual women, Chloe and Lily, who are going to wear these garments, and they also have to look good in them. They have to feel comfortable when they're wearing it, while also reflecting the character.

T: Anne’s sketches in the film, did they already exist or did you illustrate them for the film?

C: I sent them a bunch of things that existed and also sketched new ones.

T: I saw some of your illustrations on Rookie’s site, as well. It was wonderful to see the evolution of your work.

C: My god, I forgot. I was talking to a friend recently who said she was obsessed with Rookie. I was like, how do you even know what Rookie is, because she's Lebanese. I was really surprised that she knew what it was. It compelled me to go look at the site.

I loved Rookie. It was an amazing community. That’s where the OGs started: you had Laia (Garcia-Furtado), who's at Vogue now. My friend Dana Boulos was a photographer for Rookie in the beginning. There was also (artist) Maria-Ines (Gul). We all ended up meeting somehow and becoming friends. It was a very, very rare community.

T: I don't think something like that exists anymore.

C: No, because there's only one Tavi Gevinson in the world. There aren’t any other twelve year olds starting a magazine.

T: How did you get into Rookie, and how did you start doing work for them?

C: I just emailed them. I don't remember how I found out about it, maybe through Tavi’s blog. I loved what she was doing and wanted to be involved somehow. Never in my life did I think they would answer me.

T: I wanted to write for them, but I was afraid to email them.

C: No, they actually answered. I was so shocked. Everyone was on an email and everyone was so excited. I did an illustration for them that said “Rookie”, and they were like, that's the logo!

T: You're behind the logo! That's so cool!

C: All the fonts, all the handwritten stuff, the logo. I did lots of little icons. For the first iteration of the site, everything was handwritten.

T: Can you share what your inspirations are for the Spring/Summer 2026 collection?

C: I was thinking about what I miss and what I like about fashion sometimes is that it's aspirational, like the way we were talking about our childhood. I love that fashion was aspirational, creating these characters, something not really reachable. What's aspirational to me right now at this point in my life? Sleep. That is my major aspiration in life: to get some sleep, to get some fucking rest. That's probably the biggest luxury right now.

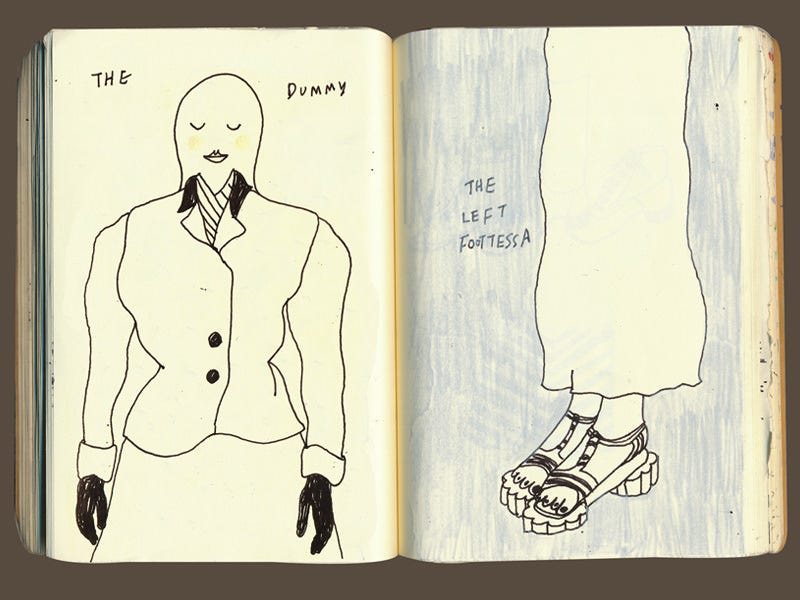

T: I was reading about how for Fall/Winter 2025, you had an alter ego.

C: I was looking at this idea of alter ego, exploring my queerness, and this idea of are you in love with her or do you want to be her? I came up with the story of this woman who is very buttoned-up and elegant. She starts seeing this other woman around town as she's doing her errands. The other woman feels a bit more relaxed, more free with herself. The first woman becomes obsessed with her and follows her around town, eventually following her into a club, where she comes face to face with her and realizes, it's her.

It's this idea that you're both these people. I looked at it through the construction of the garments and how through one garment you can transform it from very strict to something loose and unbuttoned. The way you place the button on the garment can turn it from something very free to something strict.

T: I think it’s very interesting how women observe each other, not exactly consuming each other. You don't know if they're in love with each other…

C: You don't know if they admire each other. Or are you in love with her? Do you just want to be her? I think we have a lot of power as women that we don't realize. I'm starting to see more and more women dressing for themselves, which is really interesting, moving out of the patriarchal norms.

My older sister was here for a week and she's very straight and she asked me to style her. I'd style her and didn’t realize it wasn’t attractive to men, because I'm not thinking what's going to be attractive to men when I'm getting dressed. I'm thinking, what do I want to wear? What I feel. What's my mood? Am I feeling boyish? Am I feeling girlish? Am I feeling lazy? Am I feeling like I want to get dressed up? I put my sister in a t-shirt, jeans, and black loafers, and she said, I don’t feel sexy, I look like a man. And I said, but you look so sexy!

There's also a lot that we can learn from each other's idea of what is and isn't sexy. I think it's a lot more fun when it's loose, and you can play around from both sides. I play a lot with the idea of what is sexy in my work. It's something I ask a lot, because what is sexy when you're removing it from the male gaze, when it's not in relation to a man. We're so used to sexy being something that's sexy to a man. But what is sexy for a woman?

T: I have a pair of black trousers made by you. I was fatigued by trying to find a good pair of black pants, and when I tried them on, I thought, this is somebody who actually thinks about a woman’s body when they're designing clothes!

C: I think about fit more deeply because of the way I grew up. My role model is a woman designer, my mum. If I don't think of something, she will think of it. I learned about fit from my mum, and that way of thinking is invaluable. She started her own business, she did everything on her own. I grew up with two sisters and my mum, my dad was working abroad, and my grandmothers were around all the time. It was a very matriarchal environment.

We talked about what my mom would force me to wear as a kid. I also didn’t ever want to go through that again, things like itchy fabric or something cutting you in the wrong place. When I wear something, I want to feel free. And I want every woman to feel free, even if she's wearing a ballgown, like that dress that Cécile’s wearing in the movie. It's super light. It's designed to be really comfortable. She can still move. She can still dance. I do a lot of things that are a bit dressier, but they're still very comfy.

I can attest to this because I've worn a lot of my things when I go to events. I want to feel good, but I want to feel comfortable. The last thing I want to be thinking about is the outfit. I don't want to feel itchy or that I'm sweating in it or it’s cut in the wrong place. This is what goes on in my mind. I’m very sensitive to those things.

T: It's a very brilliant mind.

C: No! Ask my mom, it's not. She’ll laugh. She’ll be like, okay…

This conversation has been edited and condensed.

Resilience needs to be added to their name for continuing to design (and beautifully) with what Lebanon is going through…