047: A Conversation with Durga Chew-Bose (Pt. I)

The director and writer on her debut film Bonjour Tristesse and creating art in the midst of life.

Though we had never met before prior to this interview, I have long felt a certain closeness with writer and filmmaker Durga Chew-Bose. We share a mother tongue: Bangla, her’s by way of Kolkata, mine from north-east and central Bangladesh. And it is my experience that when one Bangla-speaking person encounters another, far from the source, there is an almost reflexive assumption of kinship.

Durga’s masterful use of language, as demonstrated in her robust portfolio of work for publications such as The Guardian, n+1, and Paper, as well as her celebrated collection of essays Too Much and Not the Mood, has the unique capacity of stirring intimacies with readers, her quietly assertive delivery of prose leaves one pondering her work hours and even years after they’ve been read. Resisting the demand to submit to instant gratification, the writer much prefers the gradual peeling back of layers. That is, after all, how closeness is forged, how a scent lingers in the memory years from now.

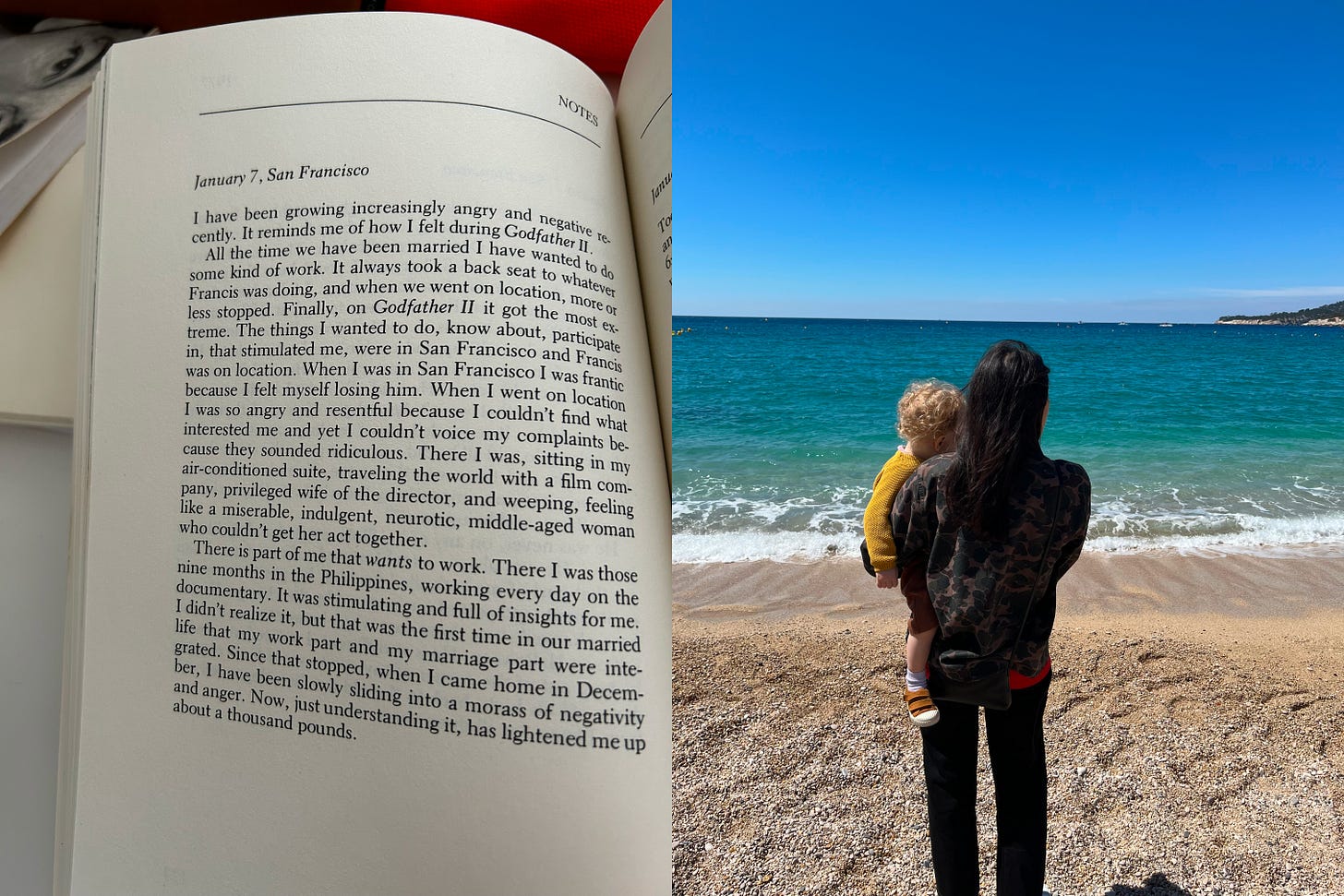

After our conversation, I was fortunate to preview Durga’s first film, Bonjour Tristesse, an adaptation of the novel by Françoise Sagan, and which stars Lily McInerny, Chloë Sevigny, and Claes Bang. And though I did not spend an intense summer by the brilliant blue water of Cassis with the fictional characters from the film, in the weeks that have passed since my first viewing, I often think of Anne’s hands, of Raymond’s heartache, I wonder where Cécile is. Its scent lingers.

Durga spoke to me from her home in Montreal, where she resides with her husband and son, near their family. It was an overcast day in Montreal and here in New York, and Durga revealed it to be her favorite kind of weather, as it ameliorates the guilt of having to go outside. She wore a preferred faded black T-shirt, not too high on the neck and just oversized enough. Just a month shy of the theatrical release of Bonjour Tristesse, I anticipated our conversation would be abbreviated, but it was quite the opposite. Despite what was happening in the background – her husband leaving for work, a package being delivered – Durga remained ever

This is part one of our conversation; part two will be published on Monday, April 21. Bonjour Tristesse will be in theaters on May 2. A preview will be screened at L’Alliance New York on April 24.

Tasnim: I was wondering, when was the first time you read Bonjour Tristesse?

Durga: I read it a long, long time ago when I was young. It wasn't something I carried with me or informed who I was going to be. But I revisited it when I was hired to write the script. And I think in some ways it's good that it wasn't that book because I was a bit hesitant and not totally sure I was the right fit for it, which in some ways I think is the best way to approach adaptation, because it means that you're freed of certain attachments.

T: What convinced you to work on the script?

D: There's the part that was instinct, and there was the part which was the less healthy version of being a person: what will people think? And I don't really have that thought as much as I used to, but it's taken about ten years to make this film. The younger version of me was thinking about that. I was thinking more about identity at the time and thought, oh, who am I, who am I to adapt this story about a very French, very bourgeois family? I do not relate to this in any kind of superficial, but even deep way, other than certain elements, like the father-daughter relationship.

There was also a third part of me that thought, it would be unexpected. There was a part of me that was interested in okay, how can I do this with my voice. And that sort of challenge has always interested me. What is my voice, its value to myself and to others? All of that mixed together presented a sort of very delicious challenge for me, not just Sisyphean, but something that felt like I could really chew on. I've learned I'm much more comfortable in a different sandbox than the one I’m expected to be in. The film itself is a testament to that because it's really imperfect. It's my first film. It's not for everybody. A lot of people don't like it. And the reaction to it is my growing pains of being in this sandbox.

I'm a little prudish, I'm not super wild, but it's something I want to work on in my work. But the book itself was so scandalous. We're also living in a post-Euphoria time of portraying adolescence on screen. The way that I wrote Cécile is not in – even though it's a contemporary adaptation – that Euphoria world. I mention this because I think people feel a bit unsteadied by the fact that there's no club scene. There's not a lot of social media in it. I think that there's an element to the film that confuses people because I'm saying this is an adolescent woman whose feet are into womanhood at this point. And yet, it isn't a wild ride. It's a very quiet film.

T: I read some of the criticism that you're talking about, and in particular, about this Euphoria-esque teenhood experience. I found it interesting that that was the criticism, because we live in a time where adolescents spend an inordinate amount of time inside, behind screens. They're having way less sex. If anything, teenhood has become quite prudish. My own experience of adolescence was...till this day I have never been to a club. Sometimes people think that the experience of adolescence is singular. You explored the softer side of adolescence that a lot of teenagers today, and teenagers of twenty years ago, and forty years ago, actually experience, a life that isn’t a hedonistic wild ride. Adolescence is slow and bumpy, and we’re all impatiently waiting for it to end.

D: The word waiting is so accurate. It's something that Françoise Sagan captures in the book. She wasn't interested in morality, so the book has this whole other element to it that is what made it so scandalous at the time. But there's a lot of waiting and contradiction in Cécile's experience of her summer. It's just really refreshing to hear you say that, because I think it's also specific to young women in a way that...when we were on vacation with our parents, we spent all our time with adults.

T: Which is how I experienced all my family vacations.

D: Exactly. There was something really fascinating and cinematic for me about showing a young woman who spends all her time with adults. She's listening. She's like so much of this film, and what I wanted to focus on in this adaptation is how various women influence her. Cécile takes things from how Anne dresses or from how Elsa talks or from how her summer love’s mom needles the other adults. She's taking notes because she's on the cusp.

I have the belief that the film will find its people and that's more than I can ask for.

If I had made a movie by committee, and committee being by what I imagine the reception should be, that feels like really squandering your chance. I made the movie I wanted to make and that's like all you can really do. What unsettled some is that we didn't try to place it in time now. And some people need the now. They need the sentence that reflects how people talk on Twitter, or they need a certain level of topicality that addresses capital T trauma. It's not that I resisted it. It just didn't interest me in my adaptation. I think it also doesn't age well, frankly.

T: Could you expand on that?

D: I think that if you're too topical with your characters, it doesn't last. Whereas if what changes a character is more fundamental or slow, the audience can think about it days later. There were some takes that I remember choosing with my editor that are maybe not the actor's best take. But there was something about their delivery that I found kind of weird. And I found that weirdness attractive. It wakes you up when you're watching. I think the emotion is right, but there's something off. And I think that offness is what ultimately sustains a film after you watch it.

I really wanted this film to be its own thing. I think people's frustration with it is that they don't know what to do with it. And we live in a world of consumption where people know what the thing is for.

T: I was watching a clip of Jhumpa Lahiri speaking about Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, and Lahiri says it is a three hour-long film of a woman essentially doing nothing, but it's one of the most incredible films ever made. Nothing is happening, but also so much is happening. Films like Akerman’s go on to become so beloved because they focus on the minutiae of life that we tend to kind of not pay attention to. And that minutiae is so exquisite and informative.

D: Chantal Akerman's a huge North Star for me. You’re in a room with this woman, and it's hard for people to watch because of the anticipation of what she will do. This is the ultimate version of voyeurism. She's sitting on the edge of her bed, just be with her. I have always been fascinated by the conversation around beauty, beauty being lazy or just like an aesthetic crutch that has no depth. It's something that really frustrates me. It takes a lot of effort to make a beautiful frame. It's not shallow. It makes people really uncomfortable. But if you think about coming of age and being a young woman, beauty is such an urgent pursuit, which is why we sought it out.

I remember when I had meetings in pre-production with my cinematographer and my AD, when we spoke the word beauty would come up often because I tried to put myself in Cécile's point of view, and of being a young woman looking at other women. You're so curious about her comb. You're so curious about what her hair looks like up versus what it looks like down. These little things are what become so important to a young woman on how to be, especially if you're growing up without a mother. I wanted to have these overt flourishes of beauty because this is the summer Cécile is going to remember forever. And how a woman puts a clip in her hair is paramount. That's just my personal experience of watching other women.

I could see how that's easily dismissed, because if you haven't lived your life in that way, if it hasn't been mapped that way for you, you're probably thinking, why am I watching this? Why am I watching women open little trinket boxes? But for me some of these behaviors are so inherent to femininity.

T: What was the experience of writing the script like?

D: It took so many years, but I tried to approach it intuitively. I'm not a very organized writer. I don't have outlines. For this, I made an outline just so I could have scenes, because the script is such a different form, and I approached it like sewing together one image after the next image, after the next image, after the next image. There's a freedom to screenwriting that I've really taken to and also it's such an expansive form. In some ways, I think it's made my prose writing more lazy. I'm still writing a lot and taking assignments because I really believe that everything informs everything else. I'm sure this conversation you and I are having in six years or hopefully a shorter time…it will strike me while I'm writing a scene.

I say this to myself because I'm a procrastinator, so I have to assume any single thing I do is going to help me. But I also know it's true. An example of this is in the film: there's a song that plays in one scene, and it's in the film because when I was making the movie in France, my son was with me and we had a nanny that the production hired, this amazing woman named Melissa. Some days I would get home for bath time, but most times we wouldn't have wrapped the day. Melissa had made this playlist for Fran for his bath time which had these Italian pop anthems on it from the 1980s and 1990s. I would come home and it would be blasting and my eighteen-month-old would be saying words in Italian in the bath.

One day, I come home and this Italian song is playing, and it's so catchy and so immediate. I immediately texted my producers and said, "I'm sure it's going to cost a fortune, but we need this song in the movie.” It’s not a huge needle drop but I do think it adds to the scene because it's a joyful moment. But to me, it's something I hold on to. Fran is such a source of inspiration for me, clearly. I like saying this, especially when I'm talking to women, because I do feel that there's a fear of domesticity when you want to make art and a fear of having to choose. But I think it's all of life and it's all in there. And you have to stay open to it.

T: It’s lovely that you've put little Easter eggs in your film that are just for you. To anybody else, it might just be a really great song, but there's something very special from a moment of your very real life going into the art that you've created.

D: It does feel very personal. There’s so many tributes in the film to women I know, tributes to my crew. It'll always be a very personal project to me, but I think everything I do will feel kind of personal.

T: I remember when you had started working on the film that you experienced a devastating loss. What was that experience like and working in the midst of it?

D: It was really hard, but it was also impossible to experience as really hard because I just had to stay there. Production was starting in less than 48 hours. In some ways I think that was the best outcome, because once you open those doors to grief, it's really hard to go back in some ways. It was like this strange limbo.

I also feel like an extremely extraordinary thing happened, and I use the word extraordinary, even though it was the worst thing that's ever happened to me. I'm still working through this, but I sometimes think that grief is my superpower. It gives you courage in some ways. It focuses your world. So clearly, even though it's so foggy in some other ways, because even when you are dealing with extreme loss, you have to make decisions. I remember being on set and during a camera set up, looking at my phone and my brother sent me a photo of two different kurtas and asked, “Which one should we put him in?” Five minutes earlier, I was choosing what the table setting for Ann's arrival would be with the production and props team.

In some ways, the film has nothing to do with my dad and it's so different from his politics and so many things that he believed in. And I have this geeky joy about it all, that I was focused on a world that is so far away from ours. But it was really hard because it was my first film. Everyone was looking at me like, can she do it? And then my father passed, and it was like, can she really do it? But in that, conversely, there was so much love and support. I think it honestly made me a more conscientious person.

This film will always be tethered to that, but I also know that so many people sacrificed a lot to be there and I didn't want to make the movie about my loss only. But there's one scene with a father-daughter dance, and I was huddled with the monitor in this alcove near the kitchen with one of my producers, Katie. The music begins and Claes and Lily start dancing, and I just broke down. I was embarrassed, because then I had to say “cut” and climb out of this space, having clearly been crying. I remember talking to my cinematographer Max after and asked, was it bad? And he said, “No, I think these moments are important.” It created a very real set.

T: A very humanized set.

D: A very humanized set. That's the thing about death. It's so normal, but so unique to every person. I think of it more like loss at this point and absence. Had I been in my twenties, I can't even imagine, but my son was about to arrive for the filming. There was just so much life happening. One of the actors was coming with her child, as well as my producer. I mention children because I feel like everyone's arriving with real life stuff. A lot of it is not glamorous. I had a sick father. I was spending months at the hospital, caregiving. People don't talk about that.

T: No, not at all. Especially when it comes to creating art.

D: Exactly. The movie is dedicated to my dad, and sometimes when that card comes up at the end, my throat closes up. It seems so dramatic when I see the dedication card. But it was dramatic, and certainly will be for a lot of the very close team that made the film. Sometimes I wonder what it must have been like for everybody else. A lot of credit goes to everyone who was around me in making the film. I never felt stifled or too doted on or treated like I was like this paper thin human either.

It's basically a miracle this movie was made. It's basically a miracle any movie is made. I definitely have even more respect when I watch movies now.

What a special conversation.

This is such a beautiful interview. It makes me very excited to see the movie and all that comes next.